Glacial water supply

Studies of future drought risk use output from global climate models to analyse changing water availability. We know that glaciers provide a seasonally important source of fresh water in arid mountain environments, but their effect is not well captured in global climate models. What’s more, some areas that currently benefit from abundant glacial water supply may see a decline in water availability as their basin’s glaciers shrink. How can we account for changing glacial effects in our estimates of future drought risk?

In this collaborative effort, we have devised a method to consistently combine output from global climate models with output from a global glacier runoff model. We analyse the statistics of our data in many dimensions: across climate scenarios, hydrological basins, and climate models. Our results show that glaciers are an important modulator of drought risk in some basins but not in others, and that their effect is likely to persist even after this century of climate change.

Example

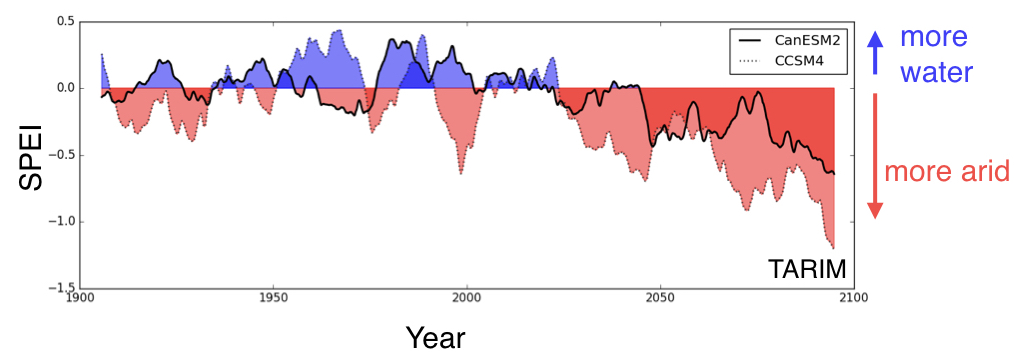

We calculated the Standardized Precipitation-Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI, a drought indicator) for 56 river basins worldwide, using eight different climate models. Below you can see 10-year running mean SPEI in the Tarim basin (central Asia), computed with the climate models CanESM2 and CCSM4. Red shaded areas (negative SPEI values) indicate more arid conditions, while blue shaded areas (positive y-values) indicate wetter conditions. Note that although the models often disagree with each other, both agree on increasing drying through the end of the 21st century.

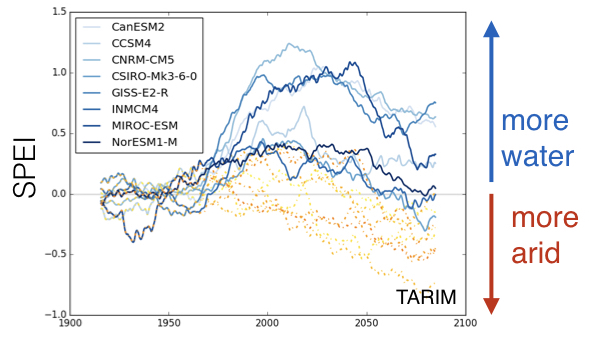

There are no dynamic mountain glaciers in the example above, so the SPEI calculation does not account for changing glacial water runoff. Now, let’s compare SPEI calculated with and without glacial runoff. The figure below shows 30-year running mean SPEI in the Tarim basin, computed with all eight climate models. Orange lines show results without glacial runoff and blue lines show results with glacial water runoff (from the model of Huss and Hock, 2018) explicitly included.

Notice that with the glacial runoff included, the models suggest wetter-than-baseline conditions for much of the 21st century, rather than the increasing drying predicted without glacial effects.

You can explore the data for all 56 basins using the Jupyter notebook and helper code in this Github repo.

Collaborators

Sloan Coats (University of Hawaii) and Jon Mackay (British Geological Survey)

Publications

Ultee, L., Coats, S., and Mackay, J. (2022). ‘Glacial runoff buffers drought through the 21st century.’ Editor’s highlight paper at Earth System Dynamics.

Extensions

Our first study found considerable inter-model spread. We aim to follow up on the structural uncertainty that creates that spread, and diagnose priority areas for improved mountain hydrology parameterizations in Earth system models.

Our 2022 study also used output from only one glacier model. Student Finn Wimberly has produced a global intercomparison of runoff projections from the three globally-capable glacier models, which will inform ongoing refinements to our work.

What’s more, we’ve assumed that liquid glacial runoff becomes immediately available in the basin. It would be great to extend our analysis in more detailed basin-scale studies, accounting for interactions between glaciers, regional hydroclimate, groundwater, and mountain wetlands.